Two years ago I was in a packed pub in Camden, watching the Olympics football, when a familiar dread overcame me. In an uncanny impression of England’s football team, Team GB were crashing out of an international tournament. In the quarter-finals. On penalties. No need for tears though since it was ‘Super Saturday’ and Team GB were having a stormer everywhere else. As I attempted to mop up the beer that an over-enthusiastic punter had launched over my replica shirt, I suddenly realised I was basically wearing a Union Jack flag. It was a strange realisation – I used to be absolutely terrified by the sight of one, writes Vinay Patel.

This was perhaps driven by the BNP being headquartered in my home borough during the early 90s. A skinhead emblazoned with a Union Jack tattoo telling you to “f*ck off home” as you made your way to the newsagents was not uncommon, and would always trigger a minor identity crisis. Furthermore, living in a southeast London that had recently witnessed the murders of teenagers Rohit Duggal and Stephen Lawrence, the possibility of insults escalating into violence didn’t seem remote.

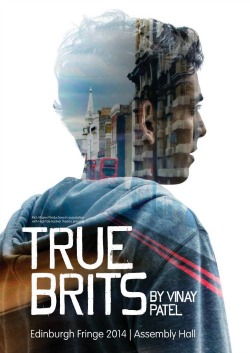

But in that pub in 2012 I stood seemingly well-integrated, flag and all. Enveloped in the euphoria of the Olympics, I felt safe and strongly British. What British was or if any of that would last, I wasn’t entirely sure. I just knew that it meant a lot to me in that moment, more than ever before. From that feeling, my play True Brits was born.

Delving into research, I found I wasn’t alone. A British Future report informed me that people of Asian descent were more likely to say Britishness was important to them than any other ethnic group, including white British. All of this in spite of the fact that the last decade had been a bumpy one for Asians in Britain, with the out-and-out ugliness of the 80s and 90s returning in new, subtler forms.

Being a young brown man in post-7/7 London meant getting used to the idea that the police were going to watch you a little more closely than others. Respectable folk at nice parties would tell you in reasoned tones that you deserved to be searched at airports. People were going to stare at you if you had a big bag on public transport, or mutter if you started growing a beard. In the worst scenario, it could get violent. It was in this claustrophobic atmosphere that I once turned to someone on a bus and said “Don’t worry about me, I’m not a Muslim,” which still stays with me as the most shameful thing I’ve ever done.

In contrast to the giddy certainties of the Olympics, during that time I’d never felt more conflicted or less connected to the country of my birth. This contrast informs the structure of the play. It is not just a juxtaposition of my feelings though; the London bombings and the Olympics are closely linked. I recall the day we won the bid. It was July 6th 2005, just one day before the bombings.

The play explores these two national events and what they tell us about ourselves. It uses a personal story, which grapples with the questions of identity that fascinate me but – crucially – makes it entertaining, engaging and relatable. A play you’d want to see, rather than feeling like one you should see.

I also avoid dabbling clumsily in extremism like so many dramas around the topic do. There is no need to when the most interesting tale I can tell is about the perverse struggle to just live a normal life at a time when all sides increasingly made that impossible. I distill all of that into one character, who goes to the darkest places that an urge to belong can lead you to and still emerges tentatively hopeful.

I want to tell this story because I am confident that modern Britain – beyond the Olympic moment – can be a place where traditional outsiders aren’t just accepted, but belong. I don’t know if we tell ourselves this enough. For me this idea sits at the base of genuine national cohesiveness. It’s the belief that this country is a place where you can freely laugh, love and live with others, where your background, gender or sexual orientation might inflect your life but wont dominate it if you don’t want it to. Only once you value that can you expect to engender collective responsibility in a diverse population. The rise of quasi-paramilitary groups like Britain First, who recently “invaded” a mosque in my home borough and intimidated an old Muslim man, demonstrates that there still exists a need for an active, progressive majority of individuals.

My family of immigrants found a home in Britain. Through their efforts, it became an even better home for me. I want to make it better still. I hope that by lionising the optimism and affection that immigrants and their descendants have found in the face of adversity, True Brits helps, even if only in a small way.

True Brits will be running at the Edinburgh Festival between 31st July and 25th August. More information and tickets can be found here.

Vinay Patel is the writer of True Brits.