Wednesday night was a very good night for Nigel Farage. The Ukip leader won the second of his two debates with deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg rather more decisively than the first. For the uncommitted, Farage won on debating style. Clegg was much too narrow on substance too. The Lib Dem leader consistently pitched only to the minority of existing liberal pro-Europeans – seeking their European votes this May – and rarely made the arguments which could well broaden that base to a majority. The Ukip leader tried harder to connect beyond his base of support. So as Farage makes the political weather, he worries pro-Europeans and cheers up those who would like Britain to get out of the EU. But should that be the other way around, asks Sunder Katwala.

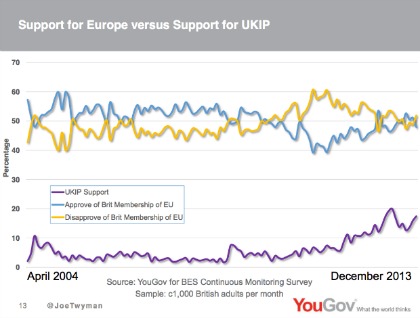

Here is the Nigel Farage paradox: the more that Ukip’s media profile, poll rating and party membership has grown over the last two years, the more that support for the party’s core mission – that Britain should leave the European Union – seems to have shrunk.

The YouGov tracker on an in/out referendum captures this Farage paradox clearly. Last year, there was an average lead for “out” over “in” of sixteen points: 48% to 32%. Since then, Nigel Farage has rarely been off the television, but the trend is now neck and neck. After Farage won the first debate, the Sunday Times/YouGov poll had a six point lead for “in”, the biggest lead for the pro-EU case for two years. The polls will continue to fluctuate, but the rise of Ukip has certainly put “in” back on level terms.

There is no doubt that Nigel Farage resonates very effectively for the one in four who are certain that Britain should leave. Those who feel most “left behind” hear their deeper discontents about how Britain has changed being voiced in mainstream politics for the first time. Yet the Ukip mood music can be a turn-off for softer Eurosceptics and “don’t knows” who are not uncomfortable with the society they live in, and risks turning those who were “leaning more out than in” back into reluctant Europeans. Hence Douglas Carswell’s timely warning to his fellow Eurosceptics that “we must change our tune to sing something that chimes with the whole country.” The libertarian Conservative argues that the “better off out” camp must offer an optimistic vision of the future, not just a reverie for a lost Britain, or what he describes as an “angry nativism”.

Immigration has driven Ukip support, which is much stronger among the one-in-four Britons who would stop all immigration if they could. Carswell says that the argument for having more control over migration needs to acknowledge that this can’t happen in the real world.

“Immigration, many Outers seem to believe, is our strongest card. It links one of the public’s number one concerns with the question of our EU membership. Perhaps. But the Out campaign must not descend into any kind of angry nativism. First and second generation Britons must feel as comfortable voting to quit the EU as those whose ancestors came over before William the Conqueror. An independent Britain is not going to have no immigration.”

Nigel Farage last night had to disown a Ukip leaflet with a Native American pictured and the slogan ‘He ignored immigration and now he lives on a reservation.’ That nativist pitch is an example of the gap between some of Ukip’s national media messages in mainstream media debates and the much harder messages being delivered in some local posters and leaflets.

Carswell is surely right that if most people think Euroscepticism is dominated by nostalgia for the past, anger about what has changed, and pessimism for the future, it has no realistic chance of persuading most Britons to make the leap.

But there are two significant challenges for this more liberal and optimistic Euroscepticism. Ukip could prosper as a party on a narrower and angrier argument. That is enough to get 10% in the polls and perhaps winning a European election, but it would be a much less effective approach in a referendum, where the target is 50% of the vote, not 30% of the narrower electorate who turn up to vote in May 2014. “Outsider” parties like Ukip have, since 1999, performed strongly in European elections and then faded when the question is who should govern Britain, as our report this week, The rise and rise of the outsider election, illustrated.

The other challenge is that this open and liberal Euroscepticism may be an even more elite project than liberal Europhilia. Among the public at large, the “better off out” case currently is resonating most with those who do prefer the past to the future, as both attitudinal and generational data suggests. The over 60s would prefer to get out – while Sunday’s YouGov poll showed a preference for in among all groups born after 1954, and so who did not cast their first votes until after Britain had joined the club. The case for “out” can’t win if it can only persuade those who can personally remember a Britain outside the EU.

This article originally appeared in the New Statesman. It has been modified for British Future.

Sunder Katwala is the director of British Future.