What the public thinks about immigration is important in British politics. It was pivotal in the electorate’s emphatic rejection of the Conservative Party in the last general election. The Conservatives lost their historic lead over Labour on immigration by losing public trust, having made high-profile promises to cut numbers and ‘stop the boats’, and delivering neither. Keir Starmer will be studying the mistakes of his predecessors and seeking not to emulate them – and keeping a close eye on how the public perceive his own government’s handling of the issue.

The Immigration Attitudes Tracker from British Future and Ipsos has followed public attitudes to immigration since 2015 and releases its new findings today. While the long-term softening of attitudes since 2015 has not been totally reversed, opinion has become more negative in the last two years, with 55% now wanting overall numbers reduced. But new questions on public perceptions of immigration cast these findings in a new light: what kinds of migrants are people thinking about when they talk about immigration? How much do those perceptions shape people’s attitudes? And what does that mean for politicians with responsibility for setting future UK policy on immigration?

When people think of ‘immigrants,’ they overwhelmingly think of people seeking asylum, rather than those coming to the UK for work, study or to live with their spouse – despite the fact that these latter categories make up far more of the UK’s immigration than asylum. Seven in ten people (70%) say they are thinking of ‘People who come here to apply for refugee status (asylum)’ when thinking of immigrants; while 46% are thinking of those who come for work, 38% mean people who come to live with their spouse and just 29% are thinking of people who come to the UK to study.

This phenomenon is most evident among those with more negative attitudes to immigration. Some 84% of ‘Migration sceptics’ – those who feel immigration has had a more negative impact on Britain – say they are thinking about people seeking asylum when they talk about immigrants, while only a quarter (25%) are thinking of those who come to the UK to work. By contrast, ‘Migration liberals’, with the most positive views of migration, are more likely to be thinking of people who come here to work (68%) than those who come seeking asylum (58%).

What the study doesn’t tell us is whether this is cause and effect – do people mostly think of asylum seekers when considering immigration, and form more negative views on that basis? Or do those negative views make people more inclined to focus on one form of immigration – asylum – more than others, like migration for work? One suspects the answer may be that both are partly the case, but it may be that further research is required.

People think asylum makes up more than five times as much of UK immigration as is actually the case, the new tracker finds. On average, the public think that people seeking asylum represent more than a third of total immigration (37%) when it actually accounts for only around seven per cent, according to the latest government figures.

Again, people with more negative views towards immigration are most likely to overestimate asylum arrivals. Four in ten Reform voters (39%) and three in ten Conservatives (31%) think more than half of UK migration is for asylum.

The public also underestimates migration for work and study, which makes up nearly 80% of migration to the UK. People think only a quarter of immigration (26%) is for work when the actual figure is around 40%; and they estimate that only 19% is for study at UK universities (actually around 38%). The tracker research finds these flows of migration tend to be more popular, with low support for cuts to people coming to do specific jobs.

It would be wrong, however, to simply dismiss concern about immigration, or asylum and Channel crossings, as founded on ignorance. The same research highlights the importance of control to the UK public when it comes to immigration, so the visible lack of control in the Channel will clearly be one reason for public anxiety. But the skewed perceptions of who is actually coming to the UK can lead to an unbalanced debate that is disproportionately focused on asylum.

That was one of the conclusions of a report earlier this year by Madeleine Sumption on her Independent Thematic Review of the Impartiality of BBC Content on Migration. This found “A substantial share of all stories in 2022 and 2023 focused on small boats and asylum. But both BBC journalists and external experts (regardless of their views on migration) questioned whether the BBC was too readily led by the political agenda, which focused heavily on small boats during the review period.”

In some respects, Sumption argues, such focus was justified: journalists must hold the government to account, and the government at the time was keen to put its pledge to ‘Stop the boats’ at the top of the news agenda. Yet her report also highlights the obvious corollary of this: more focus on one aspect of immigration, given finite airtime and journalistic staff, means less attention to other migration stories that are also important:

“Relying too heavily on political and government sources risks missing stories politicians don’t have an interest in talking about. By early 2023, it was clear that unprecedented numbers of people were coming to the UK on work visas, particularly for care work. By the spring, evidence started to emerge that some care workers faced appalling conditions in the UK, working for employers who were violating labour and immigration rules. This has arguably been one of the most striking migration developments in the UK over the past five years.”

Sumption’s review points to the extent to which politicians can often set the news agenda, and that may be one reason why we could start to see a shift over time. Keir Starmer has spoken of his desire to turn down the volume of the immigration debate and take a more technocratic approach.

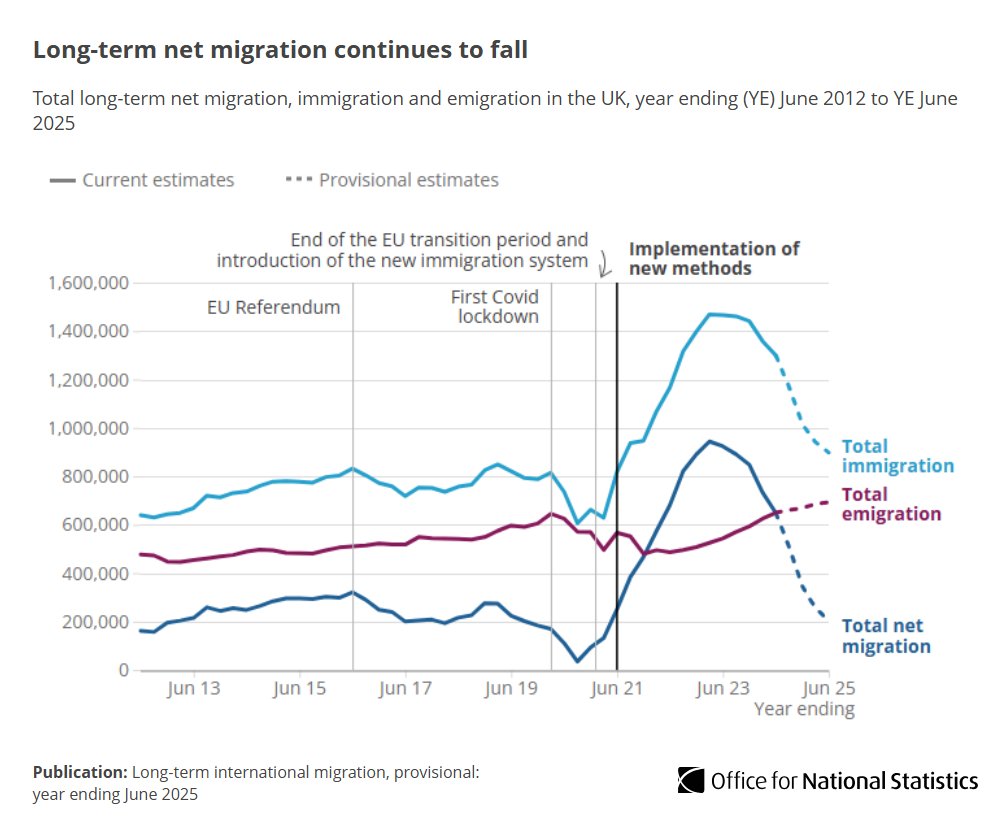

He may also get a certain amount of ‘breathing room’ on immigration as numbers start to fall – due to a mixture of changing circumstances and the policies of the previous government. Arrivals are already lower but the full impact on net migration will become evident later this year and early next. The lower numbers will come as a surprise, however, to much of the public – half of whom expect net migration to increase over the next 12 months. In fact, only 12% expect net migration to fall, according to the new tracker research. So Starmer, who has said that immigration numbers will come down under his government from recent record highs, will exceed people’s expectations.

That could open up space for a more measured debate about the immigration we have and how to manage the pressures and secure the gains. Changes to migration policy will have impacted on the numbers coming to fill health and social care vacancies, and students coming to study at UK universities – immigration that is broadly popular. Starmer may come under pressure from the care sector and higher education to ease some of the recent restrictions.

The new government acted quickly to honour its election pledge to scrap the controversial Rwanda scheme and spend the money instead on a new Border Control Force. Its longer-term efforts to forge closer ties with Europe will also seek to shift the approach to Channel crossings too. Neither will change things overnight: we will continue to see images in the news of people trying to get to the UK in small boats. And given what we now know about public perceptions, that may mean a significant fall in net migration gets little attention from a public focused on asylum. So, in the short term at least, pressure on Starmer will continue to be focused on Channel crossings – and the government will need to find a workable approach that combines compassion with control.