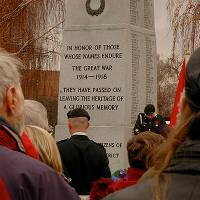

With the centenary of the commencement of the Great War approaching, an opportunity presents itself to remember, to reflect, and to renew our national understanding of the shared histories that draw us together, as well as the way we pass on those understandings and identities to our children, says school teacher Michael Merrick.

Polling shows that there are blind spots in our common awareness of the great episodes of British history, but they also show that there is no deficiency in our thirst to know more, nor indeed in our desire for our children to know more still. In this sense, history is not the sole preserve of the classroom but is something that permeates the public space. Even when contested, it is a bonding agent that helps us to better know who we are, in both the singular and the plural: the role of our town, of our community, and of our ancestors in the great episodes of British history, shaping our identities and defining our loyalties.

And yet, an important support and sometimes entrance point into these living and shared narratives is the classroom. Here, there are significant obstacles to overcome. During the first years at secondary school, too many students will receive just one hour a week of history, one hour in which to deliver an island story spanning thousands of years. One could hardly be surprised if a teacher is thereby reluctant to devote time to exploring local histories at what seems like the expense, on such a limited timetable, of a wider overview.

Neither, it should be added, is there always the guarantee that the teacher will be a subject specialist, whilst the current fashion for emphasising the forensic analysis of sources over narrative comprehension further weakens the civic-oriented impulse, turns history into a skill to be learned rather than a story to be told. Whilst the introduction of the English Baccalaureate might encourage schools to redirect more resources and attention to history, any subject fighting for extra hours in an already congested timetable, for what can appear as intangible outcomes, faces an uphill struggle.

During the centenary remembrance of the Great War, many people will gain new insight into the great sacrifices made by those who went before us, those we knew and those we did not, those from amongst our communities and those from far off places with whom we fought for a common cause. And it might also offer something further: a re-appraisal of the dynamic role history plays in shaping who we are and how we see ourselves, and how this civic aspect of history might shape the ways in which we pass it on to generations to come.

Michael Merrick is a teacher working at a Roman Catholic state school in Cumbria.